Towards more resilient and sustainable buildings - challenges and opportunities facing the post COVID-19 Estonian green building sector

Photo: (CC) Pixabay

Author: Qidi Jiang

Following the unexpected outbreak of the global pandemic of COVID-19, just like the rest of the world, the Estonian government did what had to be done to contain the spread of the virus, including a state of emergency during which people were requested to work from home and practice social distancing. Thanks to the restrict hygiene regulations, the situation has been kept well under control, but at the price of many businesses shutting down and people losing their employment. The construction sector is no exception, construction companies are predicting that the economic recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic will reach their sector in the quarters to come, once current projects start to be completed and aren't replaced with new ones.

Kristjan Mitt, a member of the Estonian Association of Construction Entrepreneurs (EEEL), suggests that the first quarter of 2020 has not shown signs of recession yet, however it will start to grow with each quarter, and be sure to continue through the first half of next year. According to Mitt, the state is considering how to move up its investments and increase its volumes, and "Perhaps it would be wiser for the state to build".

Given the fact that buildings account for 40% of energy consumption and GHG emission, increased construction investment in the public sector can play a positive role while setting up a good example for the private sector to follow, shaping a more energy efficient and environmentally friendly building sector, and thus help realize the long-term sustainable development goal set forth by the Estonian government in its 2030 Agenda in Estonia. The crisis in the building sector caused by the Coronavirus might also be the right catalyst for a more proactive and rigorous implementation of green building standards based on major green building rating systems such as LEED, BREEAM and WELL.

Demystifying green building certification

A cynic is a man who knows the price of everything but the value of nothing. -- Oscar Wilde

So why green building certification? Why Estonia? Long story short, not every building can be considered ‘green’, although every building can become a green building by implementing green building concepts and meeting certain technical criteria during the design, construction and operation phase of a building - either individually or combined. Project owners and developers investing extra money and effort in making their buildings more energy efficient and more environmentally friendly are only inspired to continue, and are able to sustain such practice if their green building projects can yield more return on investment than other normal buildings - a rather practical concern and, by and large, accurate description of the rationale propelling the green building certification trend in the world’s, and especially Estonia’s building sector. A green building certificate works in a self-explanatory way, by scientifically evaluating and verifying a building’s energy and environmental performance, and providing a score corresponding to different levels of achievement, the higher the score, the higher the level of certificate, and consequently the lower the environmental impact and the better the benefits in terms of lower operating costs, entitlement to tax incentive and funding opportunities, higher occupancy rates, higher rental rates, more streamlined/flexible compliance to future building standards, etc. In a world where economic growth is constantly contradicting the growing demand for better environment and higher living standard, a non-compulsory, market-driven practice of green building certification provides an ideal middle way in keeping such delicate balance.

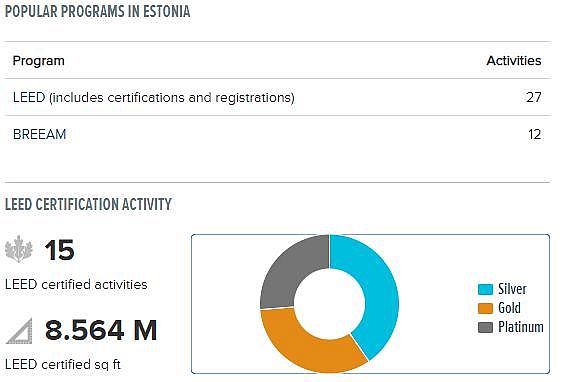

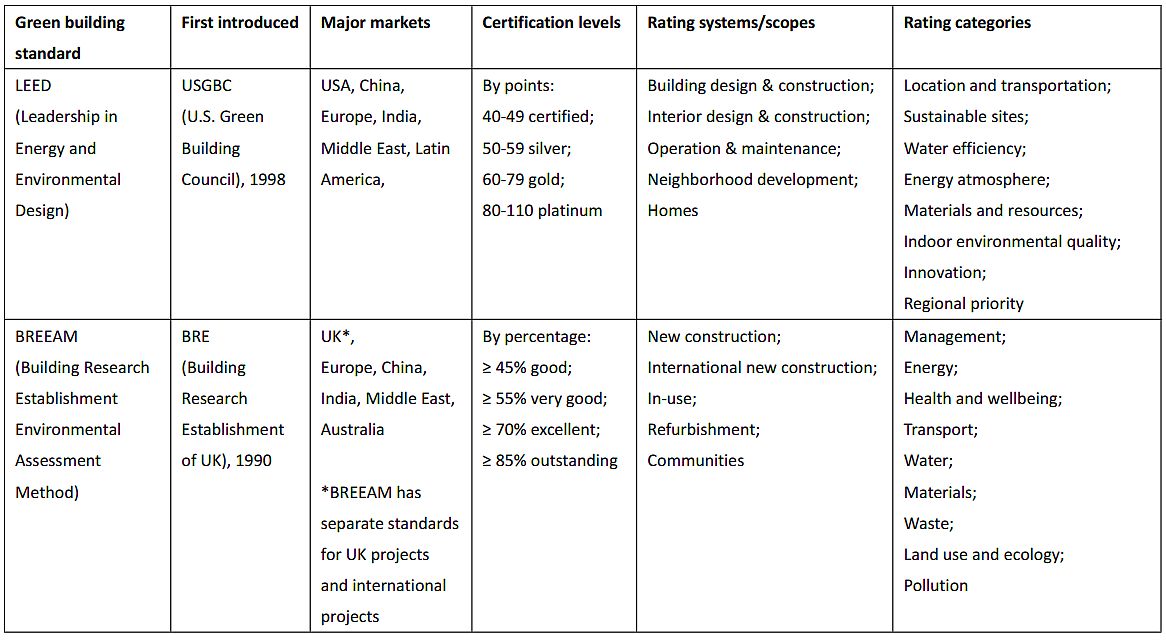

Among all major green building rating systems, LEED is the most widely adopted/recognized standard in the world, and BREEAM is the most widely adopted/recognized standard in Europe. The discrepancy of popularity between LEED and BREEAM is also well reflected in Estonia (as well as its neighboring country of Finland), where both standards are represented by quite a few projects with LEED dominating the market in terms of number of projects and total area certified.

So LEED and REEAM, which one is better? While there is no absolute answer to this question, a brief introduction and comparison between the two systems can be concluded as follow.

Notice the appalling resemblance between these two standards? As a matter of fact, LEED was inspired by BREEAM, and these two standards have in general 70%-80% in common. Yet there are unique characteristics distinguishing them:

For LEED, under each rating system the total score is always 110, but each rating category might contain different number of points (e.g. under the Building Design & Construction system, the water efficiency category has a total of 11 points, whereas under the Interior Design & Construction system, the water efficiency category has a total of 12 points, meaning different categories are given different emphasis under different systems based on the project’s nature). In BREEAM, each scope is given different emphasis and therefore accounts for different percentage not only based on the nature of the project, but also based on the location of the project (e.g. for a New Construction project in the Middle East and a New Construction project in Estonia, although both projects will adopt the same rating scope with same rating categories, the former will have a significantly higher emphasis on water efficiency compare to the latter, due to the fact that water scarcity is a much more pressing issue in the Middle East than it is in Estonia). For LEED, out of all 110 points under each rating system, 100 points contribute to a fixed scoring template and additional 10 points can be earned by adopting strategies contributing to innovation and regional priority. BREEAM however, allows a country to best adopt the BREEAM standard by modifying it into a tailored, country-specific version of BREEAM compiled in local language and practised by NSO (National Scheme Operator) licensed by BRE. So far, several European countries have their own NSO’s and country-specific BREEAM standard, such as the Netherlands (BREEAM NL), Norway (BREEAM NOR), Sweden (BREEAM SE), Germany (BREEAM DE), Spain (BREEAM ES), Austria (BREEAM AT) and Switzerland (BREEAM CH) - in addition to the BREEAM standards used specifically in UK and the international standards used for countries with no NSO’s. In other words, LEED has more standardized scoring templates which can be easily adopted by projects all over the world, each project can earn a certificate by fulfilling the scoring template, and choose to earn extra points contributed to regional priority and thus hopefully level-up its certification level, BREEAM has a more flexible and complicated scoring system tailored to different regions and countries, and regional priority is an integrated part of a localized unique scoring scheme. When it comes to registering a project for certification, while it is usually advised to have a LEED AP (Accredited Professional) as part of the project team, which will not only help coordinate the synergy between different stakeholders but also streamline the certification process, an AP is not a must-have and any project team can register and apply for LEED certification, and all LEED projects are evaluated and certified by GBCI (Green Building Certification Institute), a USGBC institution based in Washington DC. For BREEAM however, a project team must appoint a licensed BREEAM Assessor to register and evaluate the project, a BREEAM Assessor is responsible for reviewing the project information and determining the compliance, and upon finishing such process, the assessor will submit the project to BRE for certification decision. A BREEAM AP (Accredited Professional) works as a consultant in providing instructions to assist a project team in meeting the scoring criteria set forth by the project’s BREEAM scope, and to avoid conflict of interest, a project team must not appoint both roles of BREEAM Assessor and BREEAM AP to the same individual, although an individual can be a BREEAM Assessor and a BREEAM AP at the same time.

To sum up, there is no straight forward way to compare LEED and BREEAM and tell which is better given the fact that they do adopt similar strategies and comprehensively cover all building types and all stages of a building’s life cycle. However, BREEAM does allow better integration into a country’s own building standard especially when a localized version of BREEAM standard is available and NSO’s are present. LEED however, provides more universal scoring templates that are easier to follow and easier for project teams to implement and scale up to multiple buildings.

A good analogy to describe the difference between BREEAM and LEED is the user experience between Android and Apple devices, while the former enable more creative use and personalized adaptation, the latter do provide a smoother user journey and hassle-free solutions. For developers who are not completely familiar with green building standards, and not fully confident about the performance of a green building, the benefits of a green building and the to-do list of how to certify a green building can be easier communicated through LEED than BREEAM, making it more preferable for developers to adopt. In other words, LEED does do better at selling its value to the market, and this is one of the reasons why LEED has an overall better global market penetration than BREEAM and became the dominant green building standard in markets like Finland and Estonia, which does not seem to be a mere coincidence, considering both countries have no local version of BREEAM standard and NSO’s are not present.

LEED in Estonia - common misconceptions

The ship wherein Theseus and the youth of Athens returned from Crete had thirty oars, and was preserved by the Athenians down even to the time of Demetrius Phalereus, for they took away the old planks as they decayed, putting in new and stronger timber in their places, insomuch that this ship became a standing example among the philosophers, for the logical question of things that grow; one side holding that the ship remained the same, and the other contending that it was not the same. — Plutarch, Theseus

Now, think of LEED as that ship undergoing constant replacement of its parts, by the time when a whole new version of LEED is announced, will it be the same standard it used to be? The answer is no. LEED in its essence as a technical guidance is nowhere nearly as complicated as the philosophical argument documented by Plutarch. However, many misconceptions about LEED do exist in the Estonian market albeit its popular use, such irony is part of the reason why this article is written.

Prior to 2019, most, if not all of certified LEED projects in Estonia were under the 2009 version of the LEED standard, also known as LEED2009, although a much more advanced version of LEED known as LEEDv4 was already introduced by USGBC in 2013. Why? There are several reasons contributing to such delay. To start with, the first LEED certified project in Estonia, the Rocca Al Mare Shopping Center was using an even older version of LEED (LEED 2.0) back in 2010, so when developers in Estonia were later exposed to the then most up-to-date version of LEED2009, they tended to stick to it, and these LEED2009 projects (e.g. the Navigator Building, the Explorer Building, the Öpiku Office Tower A and B, etc.) are actually where local Estonian companies providing LEED certification services getting most of their first hand know-how and experience from. It is reasonable to believe that in a small market like Estonia, developers looking for LEED certification for their projects would look at existing LEED projects as benchmarks and purchase service from local companies who knew and only knew LEED2009. When I first started working on LEED projects in Estonia in 2017, I was surprised to find out that all ongoing LEED certification at that time were under LEED2009, while all my knowledge and professional credential about LEED were based on LEEDv4, a rather rare sight to behold where one’s skill set precedes the development of the local green building market, an industry which is otherwise always associated with state of the art technology and the latest standard. Fortunately, LEED2009 was officially phased out by USGBC as of November 2016, any new projects registered after that can only be assessed and certified as per the latest standard of LEEDv4. This update in the LEED standard is clearly reflected in the statistics of total registered LEED projects in Estonia, the year 2015 marked a drastic increase of total registered number of LEED projects, between March and December of 2015, the number increased from 5 to 11, in other words, 6 new projects were registered within 9 months during that year alone, doubling the total number of projects, whereas between December 2015 and July 2017, only 4 more projects were registered. It is believed that many developers chose to register their projects under LEED2009, a more lenient, less technical demanding standard compared to LEEDv4, before the official phase-out of LEED2009 in 2016. This surge in new registration and the the sudden drop following it corresponds to the fact that the Estonian market knows, or/and cares little about what LEED really does, no more than having a green badge on their building, as long as it’s a LEED, no matter how updated/outdated it is. Yet, the misconception doesn’t end just here.

Although previous experience with LEED projects does give merit to a company that provides LEED certification service, it is worth noticing that a company’s USGBC membership says absolutely nothing about a company’s actual competence in LEED. Just like a gym membership tells nothing about the fitness of a gym member, a USGBC membership is nothing but a commercial service offered by USGBC to companies wanting to promote their business in the green building certification field. By paying an annual membership of 450, 1500, 5000, or 20000 USD, any company can be recognized by USGBC as an Organizational, Silver, Gold, or Platinum member, and each level is entitled to different benefits and level of exposure in the LEED certification business. What truly demonstrates a company’s competence in LEED other than its previous project experience with older version of LEED, is the actual know-how of LEED possessed by its LEED specialist.

For LEED, just like BREEAM, there are two types of professional credentials, but unlike BREEAM Assessor and BREEAM AP, which are two parallel types of credentials focusing on different sides of a project, the two types of LEED credentials follow a clear hierarchy, they are LEED GA (Green Associate) and LEED AP (Accredited Professional). Think of GA as a freshman year student who just finished his general studies and knows about all the core concepts and fundamentals of LEED.

An AP however, is like a college graduate with a specific major of expertise in a certain type of LEED system. An AP’s credential can only be earned after earning a GA by demonstrating competence in specific area(s) of LEED. There are in total fiver different types of LEED AP, each corresponding to one specific type of LEED standard, they are: LEED AP BD+C (Building Design & Construction), LEED AP O+M (Operation & Maintenance), LEED AP ID+C (Interior Design & Construction), LEED AP ND (Neighbourhood Development) and LEED AP for Homes, each AP has to be earned separately. I have been the first, and the one and only LEED AP in Estonia since 2018, and this year, I am glad to see that Estonia finally has its second LEED AP and I am no longer alone, this sends a rather positive signal as the LEED market in Estonia continues to grow and mature.

Hopefully in the near future, when developers in Estonia are seeking LEED certification from local service providers, they will have the following critical thinking in mind: 1. Apart from previous project experience, how much does the company actually know about the latest LEED standard? 2. Does the company have anything other than a USGBC membership to associate itself with LEED? 3. Does the company have any LEED AP working for them?

To assist further reading about LEED based on this article, I have also compiled an infographic chart summarizing the LEEDv4 standard and its different systems. This will help readers better understand the LEED standard, and make informed decision when choosing to pursue LEED certification.

WELL - beyond green building, towards a healthier built environment

Architecture is nothing but the rigorous use of common sense. - Alejandro Aravena, winner of the 2016 Pritzker Architecture Prize

To end this article, I would like to discuss the WELL standard, a standard featuring the latest concepts and future development of green building certification, one that is not yet present in the Estonian green building certification scene.

Average human being spends almost 90% of his lifetime indoors, built environment is the vehicle in which most human activities and interactions take place, so a healthy built environment is crucial to the overall health, well being and productivity of its occupants. However, if we look at green building standards like LEED and BREEAM, most of their focus are placed on a building’s impact over the environment in terms of sustainable sites, energy use, GHG emission, water consumption, waste management etc., but little attention is paid to the building occupants.

There have been plenty of cases in which we see green buildings with bulky insulation and minutely small operable windows in exchange of air tightness and heating/cooling efficiency, whose indoor air quality has to be compensated by mechanical ventilation, or buildings with their solar shading and interior lighting fully automated by pre-programmed sensors sometimes working in a way that just doesn’t make much sense, or ultra-saving water fixtures causing under-flushing and clogging of sewage, etc. The good environmental intention of a green building might be undermined if it contradicts its core and fundamental purpose - to better facilitate the activities of building occupants. A green building cannot be a genuinely good building without taking humanity into consideration. It is with such concern, a group of former USGBC specialists founded the International WELL Building Institute (IWBI) in 2013 and introduced the WELL building standard, the world’s first green building rating system that focuses exclusively on building occupants instead of the building. So far, there have been over 4300 WELL projects in over 62 countries with over 5000 WELL AP’s working worldwide.

Unlike LEED or BREEAM, all of WELL’s scoring categories are built exclusively around human health factors. In the most commonly implemented version of the WELL standard - WELL v1 (the WELL standard is undergoing raid update and iteration with the latest version being WELL v2 Pilot), there are 7 scoring categories corresponding to key human needs regarding physical and mental healthy, which include Air, Water, Nourishment, Light, Fitness, Comfort and Mind, in total they are consist of over 100 measurement parameters. Based on the tick-offs from that to-do list, a project will earn different points corresponding to different levels of WELL certification. The scoring scheme largely resembles LEED, but there are characteristics that are unique to WELL. As mentioned, WELL is developed mostly by LEED specialists, so although the standard has a totally different focus, it doesn’t contradict LEED in its actual implementation, on the contrary, by and large conforms with not only LEED, but also BREEAM and other green building standards by specifying crosswalks between WELL and other green building standards, creating a synergy for achieving both a green and healthy building. In other words, buildings meeting LEED or BREEAM scoring criteria will find it easier to meet WELL scoring criteria and vice versa. Also, WELL has a much more flexible scale for certification compared to LEED and BREEAM, which mostly certify the entire building. WELL however, is particularly popular with company premises as it allows certification of a tenant space within a building, which means, for a building not pursuing any green building certification, part of it can still be certified under the WELL standard, and this certified space can work as a good example for other spaces or buildings to follow by demonstrating the optimal synergy between a green building and a healthy building. As a matter of fact, most WELL certified projects are office spaces or company HQ’s, whose total area is usually only a fraction of that of a typical LEED or BREEAM project. For example, the first WELL certified project in the Nordic area is the HQ of Green Building Partners, a Finnish company based in Helsinki, with a total area just over 300 square meters. More and more big companies and banks are also adopting WELL to make their workplace a healthier space which promotes the performance and happiness of their employees, who are the most valuable asset a company can have. For Estonia, a country globally known for its vibrant startup ecosystem which gave rise to star hi-tech companies like Skype, Pipedrive, Transferwise, Bolt, etc., WELL can provide a perfect solution through which a company can have happier and more productive employees, while also demonstrate their commitment to environmental protection and fulfillment of CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility). In my humble opinion, a WELL certified project can greatly benefit entities like Mektory of TalTech or Bolt, whose global outreach of excellence should be not only prominent in their technology, but also in how they run their place by caring for their people and the environment. Countries around Estonia have all been ambitious with projects registered or certified under WELL, Lithuania is the first Baltic country to have WELL projects, Latvia has the largest registered WELL project in the entire Baltic Region, even though no Latvian companies or professionals can provide WELL certification service. Strangely in Estonia, the market so far knows almost nothing, and shows barely any interest about WELL, although I have been the first and the one and only WELL AP in Estonia since 2018.

Up to this point, it is not hard for me to draw a fairly short but clear conclusion about the post COVID-19 Estonian green building sector: challenges lay in the market’s hesitance to embrace the latest green building standards, in its limited knowledge about these standards, in its complacency on existing achievements (admittedly Estonia still has the largest total certified area of all Baltic Nations), and last but not least, in its total negligence of all the locally accessible resources and top professionals, which are the key to turning all the aforementioned challenges into abundant opportunities.

References

ERR. 2020. Construction Sector To Be Hit Hard, Companies Predict. [online] Available at: <https://news.err.ee/1094376/construction-sector-to-be-hit-hard-companies-predict> [Accessed 30 June 2020].

Yang, L., Yan, H. and Lam, J.C., 2014. Thermal comfort and building energy consumption implications–a review. Applied energy, 115, pp.164-173.

Klepeis, N.E., Nelson, W.C., Ott, W.R., Robinson, J.P., Tsang, A.M., Switzer, P., Behar, J.V., Hern, S.C. and Engelmann, W.H., 2001. The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): a resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology, 11(3), pp.231-252.

https://www.usgbc.org/resources/country-market-brief